As their second child, and a lesbian, I am one of the two queer sheep in mi familia. An older sister was born a year before me, and ten younger siblings came after. Private time with our parents was rare.

When the invitation came to join them at their beachside timeshare in Cabo San Lucas, I said yes. Then I let my fear wash through me. I’d hardly spoken a word to my father during my twenties and thirties. He was a volatile man who thought there was nothing wrong with whipping his kids on a regular basis.

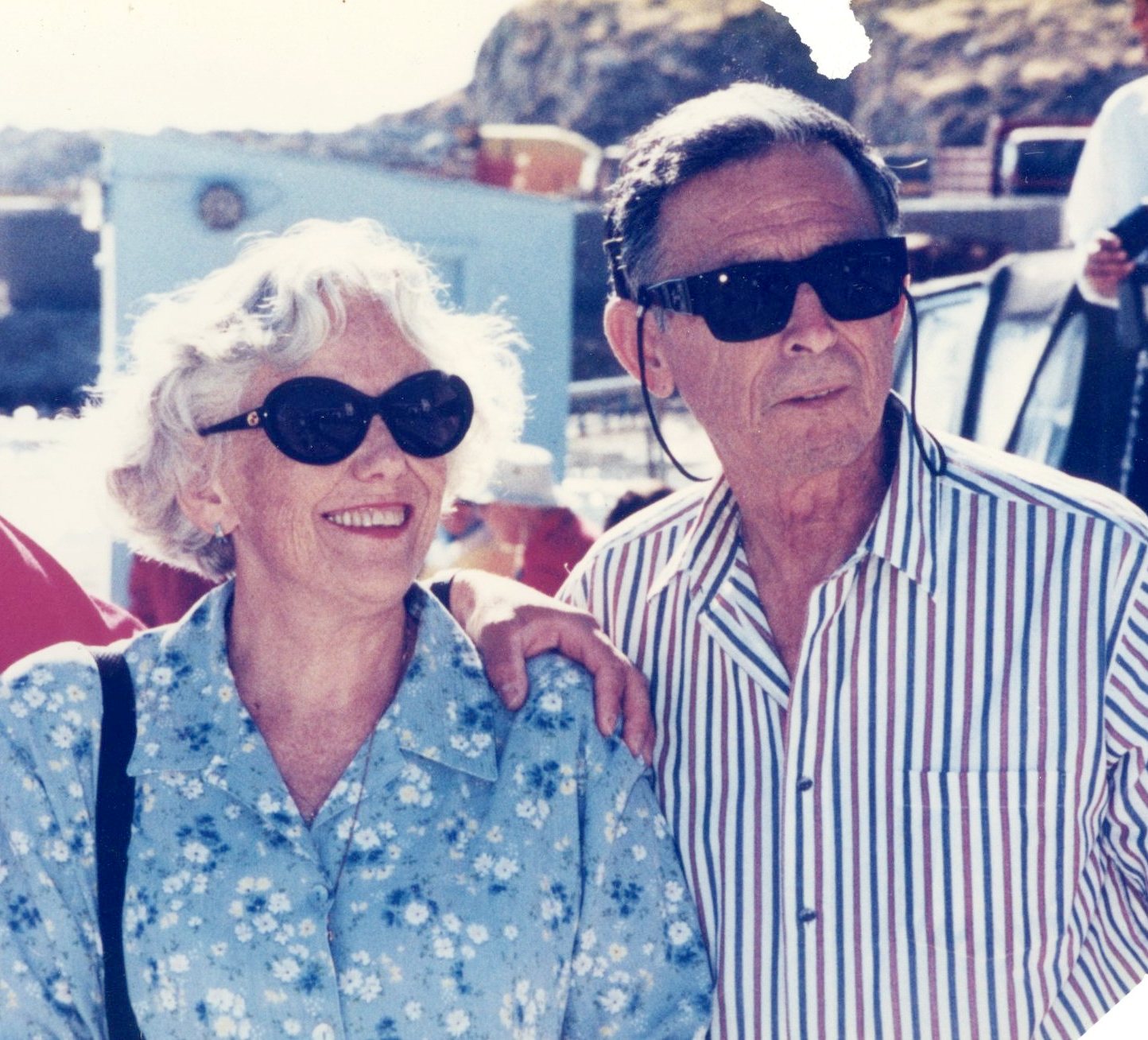

Touching down on the barren desert airport of San Jose de Los Cabos, I took hope from the tabula Blanca before me. Maybe on this bare plain I would find clearer answers about Catherine and Benedict. All I really knew of my parents was their disapproval of everything I am — a gay, Democratic, New Age, butch writer. My birthright was straight, Republican, Catholic and feminine.

The decrepit Mexican taxi rattled its way to the luxury resort where Mom escorted me and my lover, Kate, up to the penthouse. I gave up hope that anything meaningful would happen here. Too plastic. Too gringo. It seemed Kate and I would spend the week drinking and tanning ourselves into brain death.

By the second day, proximity to my father had altered my brainwaves. He kept saying and doing things, tiny things, that affected me, like when he leaned over the table and excitedly waved his hands as he told us how he’d found the best shrimp taco stand in all of Cabo. I watched him. Who else waved their left arm exactly to the right, then sharply down, to command everyone’s attention? Who else but me.

Dinner was my treat on the fourth night. My Celtic mother likes to see as little of Mexico as she can when in Mexico. She selected Carlos n’ Charlie’s for our feast.

A cold and gloomy Los Angeles winter, I was desperate to feel the sun, so I went to Mexico. I went, more urgently, because it would be the first time in my 46 years that I would be alone with my parents.

The joint is swiveling with barely clad gringa girls and pretty brown boys ebbing and flowing to the Mexican hand-jive. Cabo is sensual. The heat requires few clothes and the brown earth oozes carnality. There aren’t many dos and don’ts in Mexico, especially sexually. A few well-mixed margaritas even throw my mother into an altered state. In faultless Spanish, Dad orders a third round of especial drinks — Herradura Blanca tequila. He lifts his snifter and sways the transparent tequila under his nose. Mom and Gill think the stuff is too strong. So he and I pass the glass ritually, between ourselves. “Notice there is no odor,” he instructs me proudly. “No hang-overs from this stuff.”

I swallow slowly as the heat creeps down the back of my throat. I haven’t been this drunk in a decade.

“I would like to paraphrase one of your guys now,” my gentlemanly drunk father raising his glass to me again, “Ask not what your parents can do for you any longer, but what you children can do for us.”

I pretend not to notice a tremor on the family faultline. “What is it you had in mind?”

My father hesitates. “I shall defer to your gracious mother.” With a flourish, he yields the floor to his blue-eyed Irish wife.

“LaBamba” blares as my 68 year old mother, her eyes moistening, shouts across the table to me. “Now that our time on earth is limited, we’d like to spend more private time with you. There are so many of you.” She pauses and I see the litany of her twelve children’s faces play across her mind. “We do things together in a pack on the holidays, but we don’t get to know you individually as adults as much as we would like to.”

My eyes strain to read her lips. I’m shocked. Surely, by this point in their lives they’d had quite enough of us. The noise is deafening, but somehow apt. It was always noisy growing up.

“That’s the most important gift you can give us now,” Mom continues, “Time. Time with you. That’s why we invited you to Cabo.”

My heart turns over with joy. My face breaks into a grin. I’d thought their invitation had been business-related. My father had offered to sell me a discounted timeshare.

Mom is one of the smoothest manipulators I’ve ever known. You don’t know she has plans for you until you’ve fulfilled them. I feel proud to be had by this ploy.

So many years, months, nights of my life they weren’t there — another baby in the nursery, another sibling’s graduation eclipsing my 30th birthday, a lifestyle my father wouldn’t speak of, my political career insulted every time I mentioned it. And now, all they want is time. Conversation. To sit and talk and ultimately, to say good-bye.

“That’s not the most important thing,” my father interrupts. “Time with you is important, but tell them, Catherine. Tell them the most important thing.”

Mom shrugs bashfully. Kate leans over and shouts in my ear, “Don’t you think we should go have this kind of conversation somewhere … quieter?”

“God no!” I shout back in her ear. “They might freak out if it was quiet.”

My mother continues. “The most important thing is that you all return to the Catholic faith.” Mom is now composed. We are entering the familiar territory of metaphysics, a topic that I’d grown up with around the dinner table.

I stall for time. “Remember when we used to talk about things like the nature of the soul? How come we don’t talk politics and religion any more?”

“Let’s talk about it now,” my mother says. “Why aren’t you children Catholic? Tell me? I know you older kids are the sandwich generation. The ’60s were a terrible time. I’m sorry you were caught in that. But what went wrong, is it something we did?”

My heart sinks as I read my mother’s lips.

I am also moved by the ardor of their faith. This is the only thing that ever mattered: their Catholic faith.

Earlier in the evening my pagan lover had looked on in awe as Dad tried to convince Mom that the Beatific Vision, upon death, will be so wondrous that the body will not be necessary in Heaven.

Mom had disagreed, “The resurrection of the body is foretold in scripture,” she countered. “It’s absolutely necessary because we experience the gift of faith through our bodies as well as through the soul.”

Their eyes dance when they speak of God. How could our apostasy be their failing? I try to stem my tears. Mom had told us that we kids were her “joy” that awful Mother’s Day when she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. I, and most of my siblings, would throw our un-resurrected bodies across a freeway to save one day of her life. But we cannot give her the only thing she wants before she leaves this world.

Christ! I pray silently to God, any God. I only hope you make this come right in the final wash.

“I’d fake it for you Mom,” I swear aloud at the top of my voice. “I’d go to Mass every Sunday if you wanted. But I don’t want to insult you that way.”

“That’s not the point, Jeanne.” She echoes what I already know. “It’s a matter of faith.” My mother’s greatest gift was to instill in me the capacity for an intimate love of Spirit. We worship in the same way at different altars.

The conversation continues toward its inevitable heartbreak. Gently I tell her about my faith. Each soul must find its own way to the Love that breathes life into all of us. Yet, I know that even after four magaritas, my mother will never share my certainty that principle is greater than dogma, that belief in the Centrality of Christ is only one of highways to salvation.

Dad is the first to recognize there will be no margarita conversion tonight. He shifts in his chair to watch the blue-eyed blondes writhing on the dance floor.

“I’ll tell you one thing.” He laughs aloud but his tone remains dead serious. “If your mother goes before I do, God forbid, I’m going into a monastery — or I’m going to get myself a harem!”

We leave the tabernacle of Carlos n’ Charlie’s. Dad takes Kate’s arm as we amble into the night. I watch the poor boy turned millionaire. Dad is cut from the same dualistic cloth as Augustine and Paul of Tarsus. So Catholic, so Mexican. One extreme or the other. A harem at his age. I don’t doubt it. He’d thanked me profusely for buying dinner and boasted again about the original painting I’d purchased at an art gallery in Todos Santos that afternoon. “I wish your brother, with all his millions, had such good taste,” he had said, leaning conspiratorially close to my shoulder. “Damn shame.”

I had stiffened in my chair, shocked that Dad had complimented me over his first son. I whispered back, “Yeah, that mansion of his is a sight.”

I smile to myself as I help Mom negotiate the higgledy-piggledy sidewalks. The air is balmy, the Herradura high feels eternal. Mom and I take the lead as the four of us drift along the coast road toward home. I stumble along, now half sober. Strange that neither of them even once brought up my homosexuality. It dawns on me that they no longer see me as “gay.” Maybe they did back in the early years when I dropped the “first queer in the family” bombshell on them. How long has it been, I wonder, since they returned to seeing me as all parents see their offspring — simply as their child? Clearly I need a database update.

Back at the penthouse, Dad and Mom drop into the jacuzzi as Gill and I say goodnight.

As we head to our cabana, Dad waves, “We’ll wake you at six to go fishing!”

Kate gasps — We hate fishing. Six o’clock is three hours away!

“He’s joking,” I assure her. “It’s just his dry way of saying he had a great time.”

The stars pour the only light into our cabana. Long into the night I smile to myself, satisfied that I can finally recognize my father’s sense of humor in myself. I’d spent forty-six years hating those parts of him which I had in me: his curtness, his sexism, his sometimes savage dark side. I even hated his charm, the way my Mother was still infatuated with him, his ability to predict political developments, his blindly loyal faith in his god, his wife and his children.

Yet I had his genes. I was everything I couldn’t accept about him. And I was the poet in him — the part he had denied in order to achieve success in the business world.

Accepting him in me has also freed what is me and not him. Claiming my father has taken half a lifetime. He is not simply good or bad, frightening or childlike. He is a complex blend of paradox and emotion. I am the same, yet separate.